A team of researchers led by engineers at Tufts University’s School of Engineering and Stanford University’s Program on Water, Health and Development have developed a novel and inexpensive chlorine dispensing device that can improve the safety of drinking water in regions of the world that lack financial resources and adequate infrastructure. With no moving parts, no need for electricity, and little need for maintenance, the device releases measured quantities of chlorine into the water just before it exits the tap. It provides a quick and easy way to eliminate water-borne pathogens and reduce the spread of high mortality diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever and diarrhea.

According to the CDC, more than 1.6 million people die from diarrheal diseases every year and half of those are children. The authors suggest that the solution to this problem could be relatively simple.

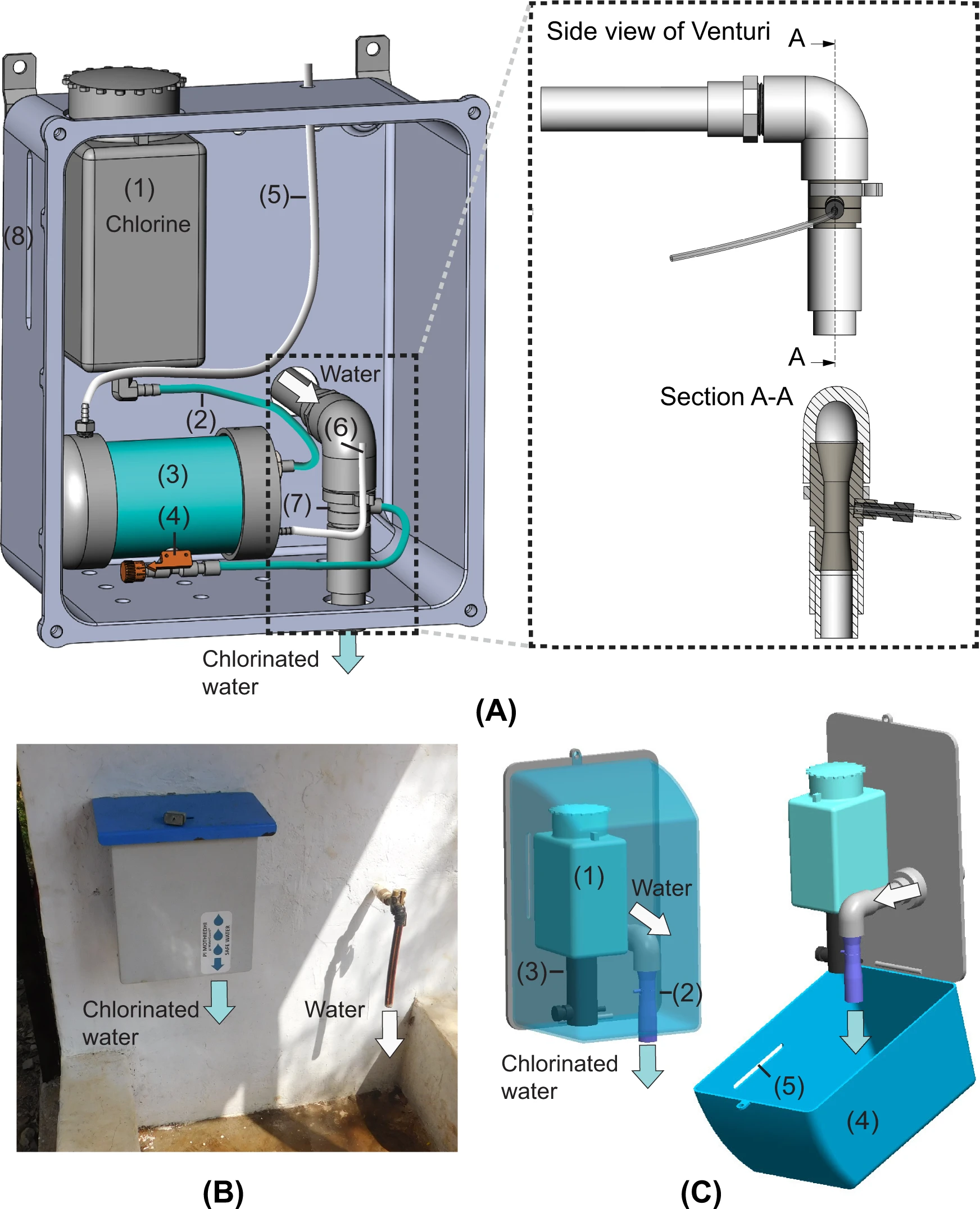

In communities and regions that do not have the resources to build water treatment plants and distribution infrastructure, the researchers found that the device can provide an effective, alternative means of water treatment at the point of collection. The device was installed and tested at several water collection stations, or kiosks, across rural areas in Kenya.

The study, which also looks at the economic feasibility and local demand for the system, was published today in the journal NPJ Clean Water.

“The idea we pursued was to minimize the user burden by automating water treatment at the point of collection,” said Amy J. Pickering, former professor of civil and environmental engineering at Tufts (now at Stanford) and corresponding author of the study. “Clean water is central to improving human health and alleviating poverty. Our goal was to design a chlorine doser that could fit onto any tap, allowing for wide-scale implementation and increasing accessibility to a higher-level of safe water service.”

Water is a simple substance, but a complex global health issue in both its availability and quality. Although it has long been a focus of the World Health Organization and other NGO’s, 2.1 billion people still lack access to safe water at home (WHO). In areas of the world where finances and infrastructure are scarce, water may be delivered to communities by pipe, boreholes or tube wells, dug wells, and springs. Unfortunately, 29 percent of the global population uses a source that fails to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) criteria for safely managed water – accessible and available when needed, and free from fecal and chemical contamination. In many places, access to safe water is out of reach due to the lack of available funds to create and support water treatment facilities.

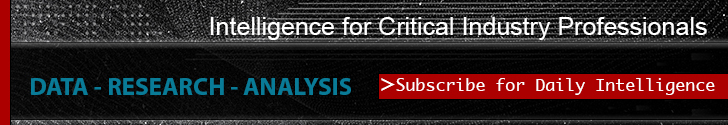

The device works on the principle of a physical phenomenon in fluid dynamics called the Venturi effect, in which a non-compressible fluid flows at a faster rate when it runs from a wider to a narrower passage. In the device, the water passes through a so-called pinch valve. The fast-moving water stream draws in chlorine from a tube attached to the pinch valve. A needle valve controls the rate and thus amount of chlorine flowing into the water stream. The simple design could allow the device to be manufactured for $35 USD at scale.

“Rather than just assume we made something that was easier to use, we conducted user surveys and tracked the performance of the devices over time,” said study co-author Jenna Davis, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford, director of Stanford’s Program on Water, Health and Development, and co-PI of the Lotus Water project. This research is an extension of Lotus Water, which aims to provide reliable and affordable disinfection services for communities most at risk of waterborne illness.

A six-month evaluation in Kenya revealed stable operation of six of seven installed devices; one malfunctioned due to accumulation of iron deposits, a problem likely solvable with a pre-filter. Six of the seven sites were able to maintain payment for and upkeep of the device, and 86.2 percent of 167 samples taken from the devices throughout the period showed chlorine above the WHO recommended minimum level to ensure safe water, and below a threshold determined for acceptable taste. Technical adjustments were required in less than 5 percent of visits by managers of the kiosks. In a survey, more than 90 percent of users said they were satisfied with the quality of the water and operation of the device.

“Other devices and methods have been used to treat water at the point of collection,” said Julie Powers, PhD student at Tufts School of Engineering and first author of the study. “but the Venturi has several advantages. Perhaps most importantly, it doesn’t change the way people collect their water or how long it takes – there’s no need for users to determine the correct dosing or spend extra time- just turn on the tap. Our hope is the low cost and high convenience will encourage widespread adoption that can lead to improved public health.”

Future work examining the effect of the in-line chlorination device on diarrhea, enteric infections, and child mortality could further catalyze investment and scaling up this technology, said Powers.