A new objective examination of almost a quarter-of-a-century of ocean acidification research shows that, despite challenges, experts in the field can have confidence in their research.

The University of Adelaide’s Professor Sean Connell from the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology unit led the study.

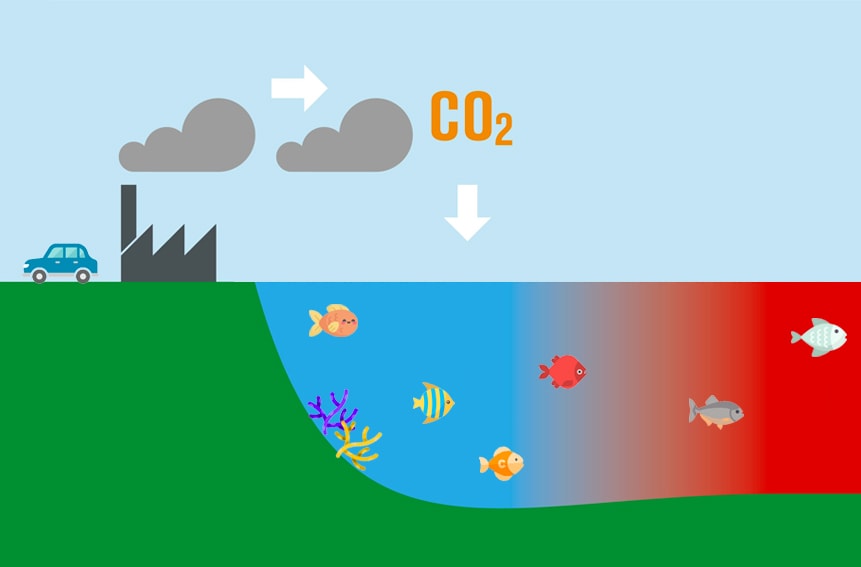

“In our field, the marine science community was galvanised by the demonstration of how ocean acidification impairs shell-building life, which has profound implications for life on the planet,” he said.

“It is an inescapable fact that ocean acidification does impose harmful effects on shell-building life.”

This field is transformational and one of the most studied single topics in marine science in recent times.

Like all scientific research, findings were subjected to intense scrutiny including how to reproduce early results. Early in the history of ocean acidification research, controversy erupted over a set of failures to reproduce its effects on key behaviours of tropical fish.

“We believe that sufficient time has passed to allow the field to look objectively into its knowledge base and rebuild confidence for the future,” said Professor Connell.

“We did so by assessing one of the largest databases in ocean acidification research – the calcification of shell-building life.”

The team assembled an exhaustive meta-analysis of calcification studies over the last 24 years.

“Pioneering studies were often marked by large negative effects, but the size of these effects declined over the years,” said Professor Connell.

“Notable exceptions seemed to highlight potential insights into less studied processes, such as compensatory dynamics.”

This new study, which is published in the prestigious journal Nature Climate Change, highlights the decline effect – a common phenomenon in many disciplines.

Results from the pioneers appeared impressive, but subsequent attempts by other researchers to replicate the same findings become less impressive as they assessed how the results reproduce in their own work.

“The key point is that the negative effects of ocean acidification remain and are frequently observed to this day,” said Professor Connell.

“In the case of ocean acidification on calcification, the discoveries of the past 24 years have been reproducible.

“The failure to reproduce large effects in pioneering studies may not represent a crisis, but most often a normal part of theory development.”

Like most human endeavours, science is subject to imperfections inherent in human nature. Humans tend to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs or knowledge, but where the scientific community fails to reproduce the same results – the theory fails and science moves on.

“Our study shows that researchers of ocean acidification can have confidence in their research community; researchers have been contributing robust data,” said Professor Connell.

“The growing pains of maturation of ocean acidification research is not so distinctive from other disciplines, their toil, setbacks and legacies.”