Why the United States announced its exclusive right over the resources in a region twice the size of California, and its implications.

On Dec. 19, 2023, the U.S. Department of State gave law of the sea watchers an early holiday present—a clarification of its claim to the U.S. extended continental shelf (ECS). The new document translates 20 years of oceanographic research into the outer limits of the U.S. continental shelf in seven areas, clarifying almost 1 million additional square kilometers of exclusive seabed rights beyond 200 nautical miles from U.S. baselines.

The Dec. 19 announcement matters—not just to law nerds, but for U.S. diplomats, environmentalists, scientists, and businesses. In one short publication, the U.S. has announced its exclusive right over the resources in a region twice the size of California. The U.S. can now choose whether to extract oil and gas reserves there or leave them in the ground. It can also decide whether to permit seabed mining in search of minerals vital to green technology, or to prioritize protecting the ecosystems found on the seafloor. Washington’s decisions on these questions will have far-reaching consequences for the American economy and global biodiversity. And how will other countries react, both to specific U.S. claims and to possible U.S. obligations under international law? When will the U.S. reach delimitation agreements with Canada, the Bahamas, and Japan?

The ECS is the section of seabed that lies beyond the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) but that is identified as part of a coastal state’s maritime entitlements based on the principle of natural prolongation. In this area, a coastal state has exclusive rights to resources on and in the seabed and jurisdiction over certain activities, particularly any form of drilling and any placement of artificial platforms.

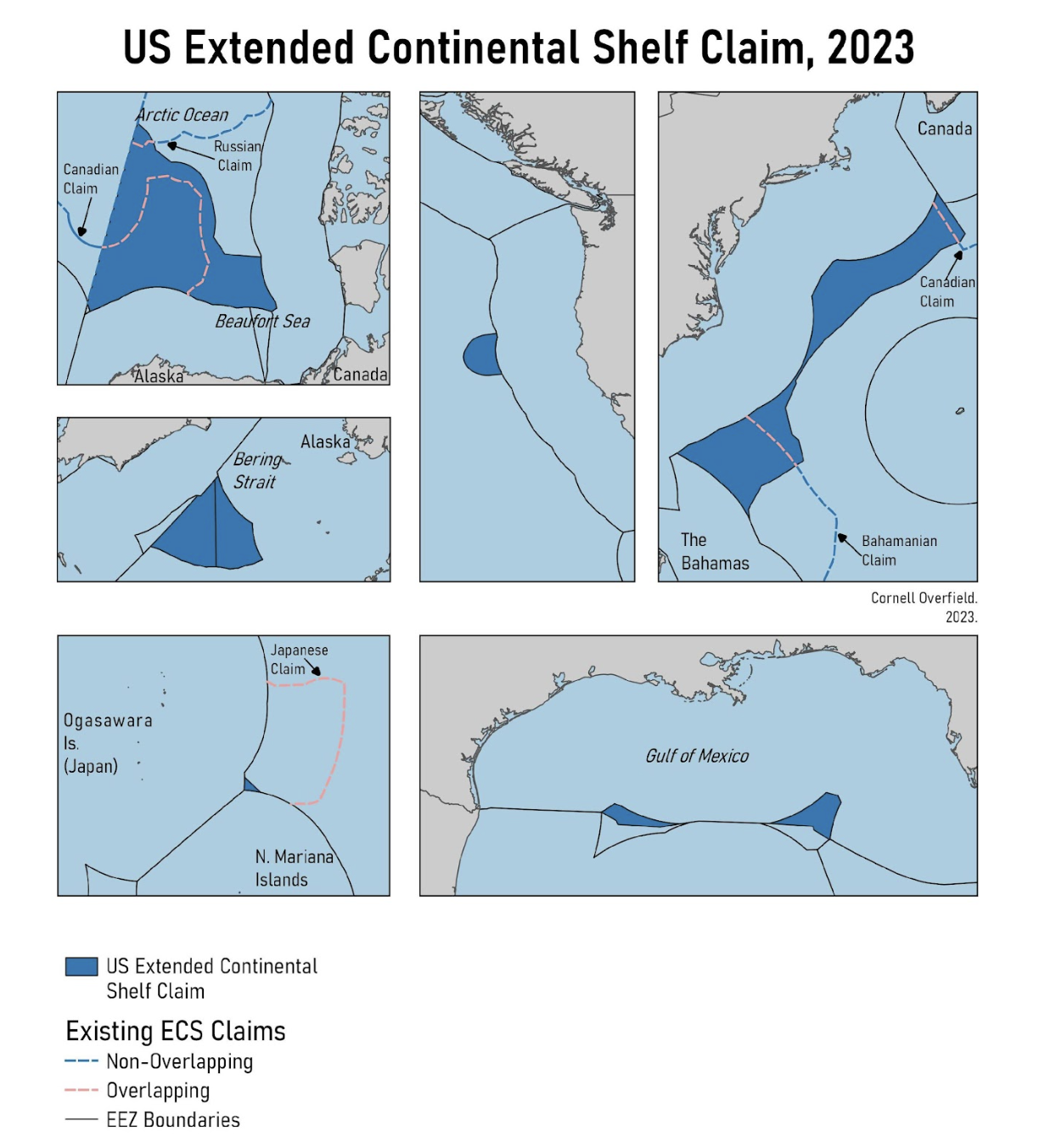

The recently published executive summary of the U.S. Extended Continental Shelf Project lays out the U.S. claim to an ECS in the Arctic, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans, as well as in the Gulf of Mexico and the Bering Strait (see Figure 1). Of the nearly 1 million square kilometers added to the U.S. shelf, less than one-quarter overlap with existing, pending claims. The U.S. Arctic and Atlantic claims partially overlap with existing Canadian and Bahamian claims, while the Mariana Islands claim fully overlaps with a Japanese claim. The relevant boundaries with Cuba (Gulf of Mexico), Mexico (Gulf of Mexico), and Russia (Bering Sea, Arctic Ocean) are already well established, with the exception of the more complicated case of Russia, which this piece will address later. The U.S. reserves the right to expand its claims, either in these areas or to new ones, depending on further data collection and analysis.

The U.S. right to a full continental shelf stretching beyond the EEZ is rooted in well-established customary international law. The announcement cites the principle that a legal continental shelf exists ipso facto (by the fact itself) and ab initio (from the beginning)—even before a coastal state charts the full extent of its entitlements. This principle, fundamental in the landmark North Sea Continental Shelf cases, is enshrined in both the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The United States has still not ratified UNCLOS, but by ratifying the 1958 convention and playing a central role in the formation of the underlying customary international law, the United States is on firm legal bedrock with its claims.

Set on this firm legal bedrock, the United States has every right to claim a full continental shelf. Some commentary has worried that other states might seize on U.S. nonratification of UNCLOS to argue that the U.S. claim is illegitimate or undermines the maritime rules-based order. These commentators should remember that it would be the states that deny the U.S. its clearly established right to a continental shelf that would be undermining maritime order and international law. In the highly unlikely event that any state takes such a position, the U.S. needs clear and consistent messaging that explains the facts.

The likelier area of debate is much narrower, but not unimportant. The U.S. has embraced the technical rules in Article 76 for determining the limits of the continental shelf—will other countries in turn argue that Article 82 reflects customary law and requires the U.S. to pay a portion of the revenues from activities on the extended shelf to other states via the International Seabed Authority?

Most importantly, the announcement clarifies the scope of the United States’ exclusive right to extract or protect seabed resources. The nonliving riches of a continental shelf most commonly include oil and gas but could potentially also include rare earth metals. The temptation, particularly in easily accessed regions (that is, not the Arctic), will be to exploit these resources, whether to fuel combustion engines or the green transition. However, the United States could instead prioritize conservation in these areas, most obviously by choosing to keep any hydrocarbons in the ground. More creative conservation measures could include extending federal restrictions on deep-sea trawling to these new shelf areas. Although the water column above the ECS remains high seas, the United States could argue that catching or destroying aquatic life living on or in the seafloor violates its exclusive rights to this biomass. Such a policy could be doubly good for the environment. Not only is trawling massively destructive to marine life, but recent research shows that it also releases large amounts of carbon sequestered in the seafloor.

As a matter of law, the announcement begins to clarify the geographic scope of U.S. jurisdiction that previously technically existed under U.S. law and the ipso facto, ab initio doctrine. In 2020, Presidential Proclamation 10071 announced the U.S. intention to exercise its jurisdiction over marine scientific research in its EEZ and continental shelf to the maximum extent possible under international law. This created a strange scenario in which certain research and economic activities would require U.S. consent, but users had no way of knowing where the U.S. shelf, and thus an obligation to seek U.S. approval, ended. This problem still exists, since the United States reserves the right to further modify its ECS claims, but is at least somewhat lessened.

Two main questions remain.

First, will the United States submit its claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) ? If yes, how will the CLCS and the international community party to UNCLOS react? The CLCS is a body established under UNCLOS to consider submitted data and make nonbinding recommendations to states on the outer limits of their shelves. However, it’s a matter of some debate whether a non-party to UNCLOS like the U.S. could go through the CLCS process. Since the CLCS has no power to set ECS limits, the U.S. does not need CLCS approval, but it would go a long way in creating the clearly agreed and acknowledged international boundaries essential for investment by extractive industries. And other states might have an incentive to allow the U.S. to join the CLCS’s lengthy queue—the commission could find fault in some of the U.S.’s data. The executive summary reflects this logic, stating that the United States is prepared to submit to the CLCS even before U.S. UNCLOS ratification, and that Canada, the Bahamas, and Japan would not block such a submission. And yet, if the U.S. does take this step, it may remove one of the common arguments in favor of U.S. ratification of UNCLOS, and strengthen the hand of those who argue that ratification would bring only downsides and costs in the form of a mandatory cut of the riches of the U.S. shelf.

Second, the overlaps could create incentives to delimit maritime boundaries ahead of CLCS delineations.

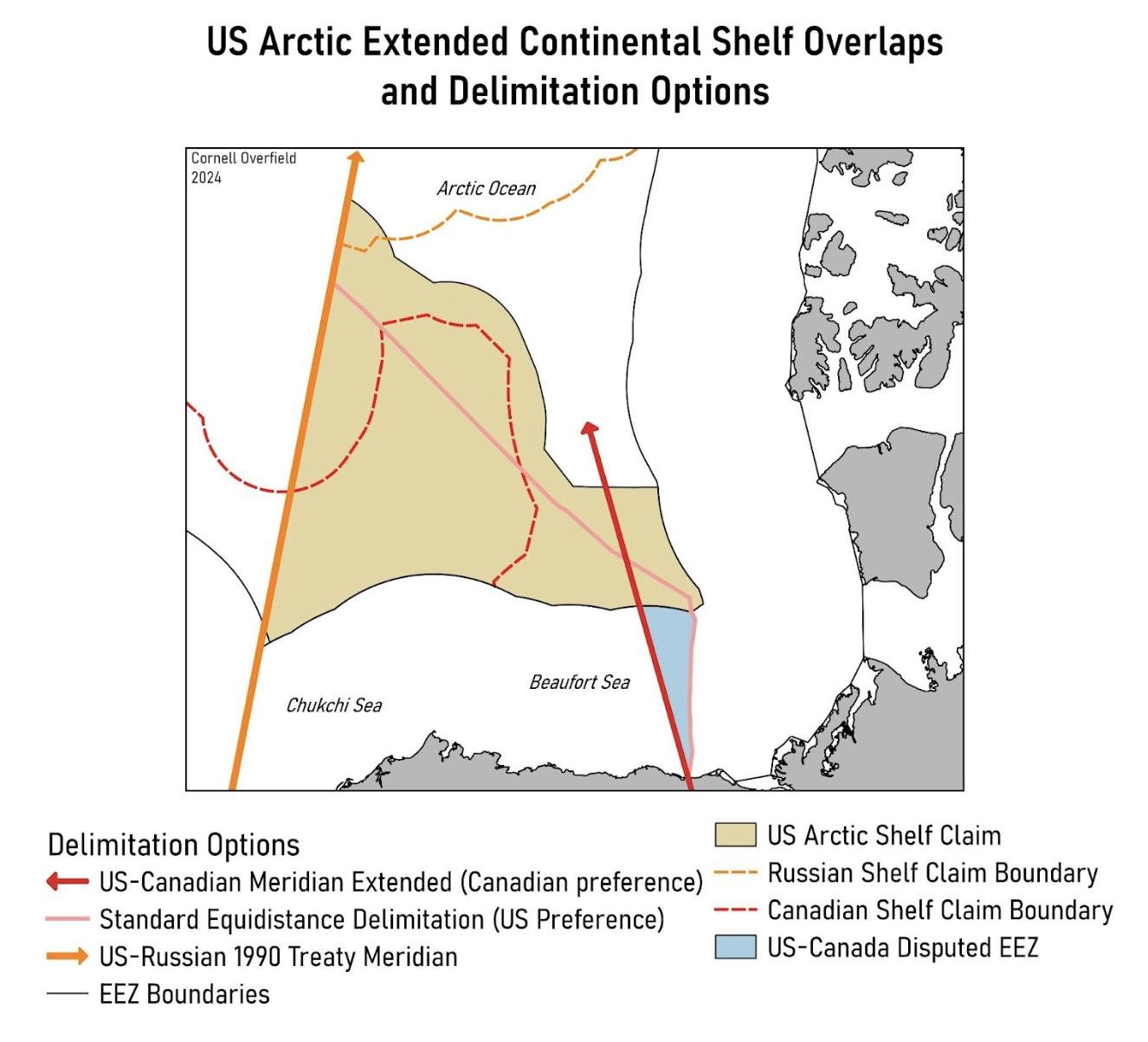

Off Alaska, which is warming at a rate two to three times the global average, the U.S. and Canada have a long-running maritime boundary dispute in the Beaufort Sea. While the Arctic will continue to be a challenging operational environment even in a warmer future, dreams of tapping the resources in the Arctic shelf might give some impetus to solving the U.S.-Canada border. Canada holds that the Alaska-Yukon border should continue straight on its meridian indefinitely, the United States maintains that regular rules of coastal projection should guide the maritime boundary. Canada’s formula would win it a larger EEZ, but the U.S. shelf claim confirms what law of the sea watchers had long suspected—the meridian approach costs Canada dearly on the seabed. With everyone’s cards on the table, hopefully Ottawa and Washington can find a compromise to settle the saga.

Although the U.S.-Russia Arctic maritime boundary is basically settled, it’s not actually settled, and the new U.S. shelf announcement sets up an interesting situation to keep an eye on. In 1990, the United States and the Soviet Union signed a treaty establishing the comprehensive maritime boundary as running north as far as applicable along the 168° 58’ 37” meridian (the orange arrow in Figure 2). The U.S. claim fully respects the 1990 treaty, in both the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Strait. While Russia has yet to ratify that treaty and some Russian politicians regularly suggest ripping it up, Moscow adheres to it as a matter of policy and practice. Moscow’s 2001 and 2015 submissions to the CLCS fully complied with this boundary. However, in 2021, Russia extended its claims across the Arctic Ocean to Canada’s EEZ boundary, crossing the meridian, and now we can see the result—a small wedge of overlap with the U.S. claim.

It seems Russia has five options to respond to the U.S. ECS claim. If Russia remains committed to a peaceful and cooperative approach to maritime delimitation in the Arctic region, it could (a) implement the 1990 treaty and shift Russia’s shelf boundary back a few nautical miles, although this is unlikely. More likely would be for Russia to (b) welcome a CLCS submission by the United States in the hopes that the commission will trim the U.S. claim or (c) wait out a U.S.-Canada delimitation (Canada also has a claim in the area) in the hopes that the area ends up on Canada’s side of the boundary. In either case, the U.S. loses its claim to the area, and Russia’s claim is once more compliant with the 1990 treaty. More assertive and confrontational responses could include (c) questioning the U.S. claim altogether or (d) taking this as an opportunity to finally break with the 1990 treaty. That the CLCS has already confirmed the Russian claim in that area as valid complicates matters. That does not preclude an equally valid U.S. claim, but it might give Russia less reason to take option (a). A rational Moscow has the most to gain from options (b) and ©, but in the current environment, even the depths of the Arctic Ocean may not be safe from the chill in relations between Russia and the West.

– Cornell Overfield is an analyst at the Center for Naval Analyses, the Navy’s federally funded research and development center. His views do not necessarily represent those of his employer. Published courtesy of Lawfare.