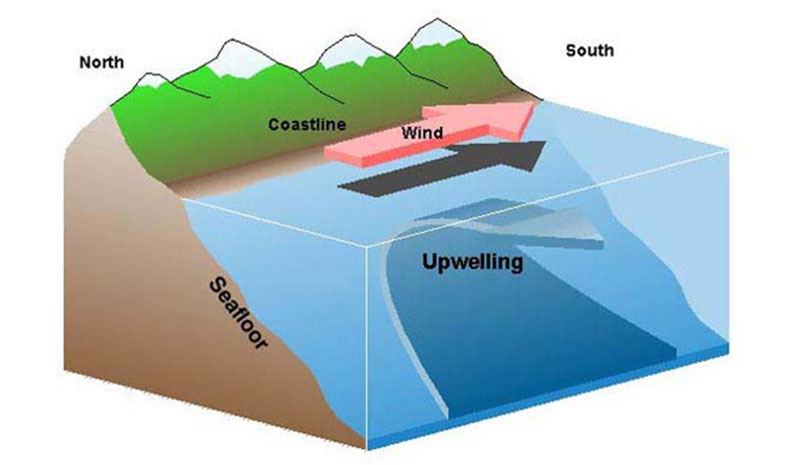

They are among the most productive and biodiverse areas of the world’s oceans: coastal upwelling regions along the eastern boundaries of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. There, equatorward winds cause near-surface water to move away from the coast. This brings cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths to the surface, inducing the growth of phytoplankton and providing the basis for a rich marine ecosystem in these regions.

In some tropical regions, however, productivity is high even when the upwelling favourable winds are weak. An international team of researchers has now investigated the physical mechanisms driving the upwelling off the coast of Angola. They found that the combination of coastal trapped waves and increased mixing on the shelf control productivity in this system. Their findings, published today in the journal Science Advances, could help predict the strength of seasonal productivity peaks.

“Productivity in the upwelling region off Angola shows strong seasonal fluctuations,” says corresponding author Mareike Körner, PhD student in the Research Unit Physical Oceanography at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. “The main upwelling season occurs in austral winter, from July to September. During this time, there is very high primary productivity in the waters off the Angolan coast, and correspondingly, there is a lot of fishing”.

Waves in the interior of the ocean play a crucial role for productivity, causing cold, nutrient-rich water to move up and down on seasonal time scales. These waves are not generated locally off the coast of Angola but originate at the equator. There, seasonal wind fluctuations create waves that travel east along the equator. Once they reach the eastern boundary of the equatorial Atlantic, they excite coastal trapped waves, which propagate polewards along the African coast. On their way, these coastal trapped waves transport nutrient-rich waters onto the Angolan shelf. Strong tidal mixing on the shelf brings the nutrients to the surface, where a phytoplankton bloom is induced. These plankton blooms can vary from year to year, depending on the intensity and arrival time of the coastal trapped waves.

For their study, the researchers combined hydrographic, oxygen, nitrate and satellite data, and a regional ocean model.

Körner emphasises: “The upwelling off Angola is caused by waves that are excited at the equator and then propagate along the African coast. This provides a potential for predicting the strength and timing of the biological productivity peak off Angola on seasonal time scales.” A better understanding of the driving mechanisms in this southwest African coastal upwelling system is also crucial for assessing possible future changes, such as the effects of climate change or other human impacts, in this important marine ecosystem.